by Chris Ritter

The Global Methodist Church inherits legacies from several denominational expressions spanning nearly 250 years. This series is designed to provide context for the weighty decisions that will be made in Costa Rica at the GMC Convening General Conference in September 2024. This second installment on Methodist episcopacy covers the first decades of a young church in an experimental nation. Part One traced the history of the first Methodist bishops and Francis Asbury’s rise as Methodism’s episcopal prototype. Although a restrictive rule was adopted in 1808 to prevent General Conference from destroying the unique Methodist “itinerant general superintendency,” subsequent generations evolved the office into forms early American Methodists would scarcely recognize. The Methodist Episcopal Church commenced with two primary centers of power: The General Conference and the Asburian episcopacy.

Two Towers

As previously noted, Asbury was a respected and forceful leader with the will to govern. In 1789, he proposed “The Council” as a replacement for General Conference. Numerical and geographic growth in the church had made a plenary meeting of the preachers unwieldy. The Council, as Asbury proposed it, would be composed of bishops and “presiding elders,” a new category invented by Asbury and appointed by the bishops. (Kirby, 52) The Council’s decisions were not binding until approved by the various conferences. Jesse Lee and James O’Kelly, members of the twelve-member Council, were nonetheless opposed to it. They noted the consolidation of power around the bishops. A requirement of consensus effectively gave Asbury veto power in all matters. The requirement that decisions be affirmed by the conferences, they feared, would compromise unity when some regions accepted changes and others did not. The Council responded to these criticisms by making its work advisory only. The requirement of unanimity was amended to 2/3 support by the bishops present. But the very concept of The Council was opposed in some conferences, especially those under O’Kelly’s influence.

By the 1792 General Conference, American Methodism had eighteen conferences and moves were made toward Jesse Lee’s suggestion of a delegated General Conference. Faced with the possibility or succession in Virginia, Asbury reluctantly agreed. The Council was abolished.

General Conference was and is powerful by design. While the U.S. Federal Government is assigned limited, enumerated powers by the U.S. constitution, the General Conference enjoys sweeping powers with minimal restrictions. Fifty years after the Methodist Episcopal Church’s establishment, Bishop Hamline argued before General Conference that “our Church constitution recognizes the episcopacy as an abstraction, and leaves this body to work it into a concrete form in any hundred or more ways we may be able to invent.” (Kirby, 48) The 1792 General Conference established that bishops would be elected at General Conference and amenable there for their conduct. Procedures were put into place for the trial of a bishop.

Appointive Authority

As today, preachers are sometimes unhappy with their assignments. At General Conference 1792, James O’Kelly recommended a process wherein preachers could appeal the bishop’s appointment to their conference for reconsideration. The debate raged for over two days. Asbury, removing himself as moderator, issued a letter to the conference:

I am happily excused from assisting to make laws by which myself I am to be governed: I have only to obey and execute. I am happy in the consideration that I never stationed a preacher through enmity, or as a punishment. I have acted for the glory of God, the good of the people, and to promote the usefulness of the preachers. (Kirby, 56)

His amendment defeated, O’Kelly left the conference reviling Asbury as a “pope.” He started the Republican Methodist Church in and around Virginia which later split over baptism and variously merged with other groups, including congregationalists.

Free to Experiment

It is sometimes said that Asbury had never met a bishop until he became one. American Methodists had no established models for episcopacy adequate for their burgeoning context. Citizens of an new nation, they felt free to experiment. The itinerant evangelistic ministry being of central importance, a primary task of Methodist bishops was to ensure its continuation.*

There were any number of legislative proposals to modify the episcopacy in the early 1800’s. The New York Conference proposed a special conference comprised of seven preachers from each conference where bishops would be elected. There were suggestions that presiding elders be elected by the annual conference rather than be appointed by the bishop. All these proposals aimed at limiting episcopal power were defeated. But others were accepted. Term limits were established for presiding elders. An 1804 rule established that no preacher should be stationed in the same place for over two years. The adoption of a delegated General Conference (the first was in 1812) perhaps brought the most significant change:

“The bishops would now sit in the assembly as presidents but not as members since they were not eligible for election by an annual conference. Asbury and McHenry largely ignored this change in status, continuing to speak and act in the conference. However it was soon established that this change logically meant that bishops were not allowed to make motions, vote, or to enjoy the privileges of the floor…Bishops now were able to rule on points of parliamentary law but not to decide points of ecclesiastical law, for the General Conference was to be the interpreter as well as the maker of church law.” (Kirby, 74)

Other Changes

When William McKendree preached powerfully at a Sunday service during the 1808 General Conference, Asbury is said to have prophetically commented, “That sermon will make him a bishop.” Bishop Whatcoat had died two years earlier and Coke was needed in England, leaving Asbury as the sole episcopal presence. McKendree, relatively unknown before his election, served as a junior bishop under Asbury and often travelled with him. But significant developments in the episcopacy are attributed to him. He began the practice of consulting with the presiding elders in the making of appointments. To Asbury’s seeming surprise, he stood at General Conference 1812 to deliver the first Episcopal Address.

General Conference 1812 came very close to approving the election (rather than the episcopal appointment) of presiding elders. The first Committee on Episcopacy is mentioned in the minutes of that conference. In 1816, the bishops were given the responsibility of devising a course of study to be followed by candidates for the ministry. “They were now established officially in the traditional episcopal function of being the teachers of the church.” (Kirby, 84.) Asbury wanted to keep the number of bishops small, but he increasingly lost that argument. As the ranks of bishops grew, they began dividing up their work of superintending in a set plan of visitation. Kirby sees this as a first step toward a modified form of diocesan episcopacy (85).

When the 1820 General Conference considered a process of electing presiding elders from three nominees offered by the bishop, Joshua Soule, newly elected to the episcopacy, refused consecration if his power was to be so limited. The matter was tabled. The same General Conference empowered the bishops to return any piece of legislation they deemed unconstitutional back to the General Conference. Like a presidential veto override, a 2/3 vote of General Conference would establish the legislation as constitutional. It would be over a hundred years before a church court was established to settle such questions.

Fractures were beginning to show by the 1820 General Conference. Bishop Joshua Soule had primarily authored the constitution and was a champion for the Asburian model of strong episcopacy. Opposite the “strict constructionists” were revisionists, Bishop Elijah Hedding among them, who favored “a loose and broad interpretation of those [constitutional] powers on the other.” (Kirby, 98) This division reflected a larger cultural divide and would lead to the formation of the Methodist Protestant Church in 1828. But a much larger separation was on the horizon.

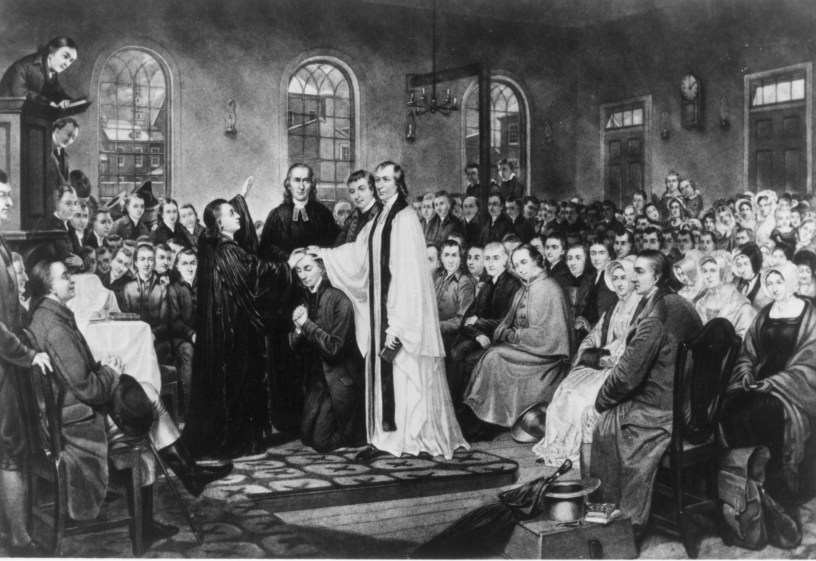

Photo Credit “The Ordination of Francis Asbury”

*When Richard Whatcoat was elected to the episcopacy in 1800, he functioned as a junior bishop assisting Asbury. When Thomas Coke proposed to return to America if the conferences were permanently divided between him and Asbury. His offer was declined.

There are several citations in this article to The Episcopacy in American Methodism by James E. Kirby (Kingswood Books, Abingdon Press), 2000. It is a recommended resource for further study.