by Chris Ritter

[See also “The Legacy of Methodist Bishops, Part One: Coke & Asbury” and “The Legacy of Methodist Bishops, Part Two: Negotiating Episcopal Power“]

In this third installment, we depart from James Kirby‘s outline of structural developments in Methodist episcopacy to consider the spiritual leadership of early Methodist bishops. There is a tendency to reduce the episcopacy to a gear in a larger denominational machine and miss that early Methodist bishops were primarily apostolic evangelists… missionaries with a mission field.

There is something of a myth that American Methodism grew naturally with an expanding nation. Growth was far from guaranteed. Methodism ran counter, in many ways, to the early American zietgeist of Enlightenment thinking. According to the Christian History Institute, American Methodist membership dropped from 67,643 to 61,351 during the last six years of the 18th Century. In the 1790’s, the population of frontier Kentucky tripled, but the Methodist membership there actually dropped. Christian faith was ebbing in America and Bishop Francis Asbury recognized this. After visiting settlers in Tennessee in 1794, he wrote, “When I reflect that not one in a hundred came here to get religion, but rather to get plenty of good land, I think it will be well if some or many do not eventually lose their souls.” Universalism (all are saved regardless of faith) and deism (the belief that the Creator is uninvolved in the world) seemed to be winning the day.

But the Nineteenth Century would belong to the Methodists and their brand of “experimental [experiential] and practical religion.” Partial credit must be laid at the feet of the early bishops who spiritually shepherded the movement that is now entrusted to us.

Preaching

Methodist preachers were an order of itinerate evangelists and none travelled wider and preached more often than their bishops. The early bishops would preach the Gospel anywhere a crowd could be gathered… barns, houses, chapels, taverns, or open country. Preaching was fiery, sincere, and themed around the evangelical doctrines of faith, repentance, justification, and sanctification. The aim was to elicit a discernible response in the hearts of the hearers under three general headings: (1) those that experienced a spiritual awakening to their need for Christ, (2) those testifying to a spiritual conversion, and (3) those who testified to an experience of greater sanctification. (“Awakening, converting, and sanctifying grace.”) There were times when the Spirit fell so heavily during singing and testifying that a sermon was spontaneously omitted. More often, the recognized presence of the Holy Spirit came as a result of preaching. Christian Newcomer, the third bishop of the United Brethren, wrote in his journal in November 1803:

“Today we had indeed a little Pentecost, from 3 to 400 persons had collected, more than the barn in which we had assembled for worship, could contain… During the time of preaching, several persons fell to the floor, some laid as if they were dead, others shook so violently that two or three men could scarcely hold them; sometimes the excitement would be so great that I had to stop speaking for several minutes, until the noise abated; some few were praising God and shouting for joy.”

Bishops were elected by preachers, in part, for their effectiveness in preaching. We have a remarkable eye-witness account by Nathan Bangs of a sermon given by William McKendree at a Sunday service adjacent to the 1808 General Conference at which he was elected bishop (included below as a footnote).*

Prayer

Reading through the journal of Francis Asbury, I was struck by how often he was sick and expected to die. Something kept him going as early Methodism’s most prominent and well travelled leader. He attributed his strength to prayer. “I pray always; prayer is my life” Asbury wrote in a 1810 journal entry. He complained elsewhere that “talking too much, and praying too little” contributed an experience of “barrenness of soul.” Among his many demands, he seemed always to be scouting a location to “enjoy sweet solitude and prayer.” John Chalmers, Asbury’s traveling companion in 1788 to 1789, recalled: “I was with him not only in the pulpit and sacramental table, but often in the closet, where I witnessed his agony and secret and long stay. I wondered why he remained so long on his knees.” A good portion of early conferences seemed to be dedicated to prayer (testimony, singing, and preaching being the other parts). Asbury most often stayed in homes and was an advocate for family prayer in every place he lodged. Prayer was more than a means to an end: “Communion with God was the summum bonum, the primary purpose of existence.” (America’s Bishop: The Life of Francis Asbury, p. 184)

The early bishops led a prayer-soaked movement that included fasting as a regular strategy whenever the need was recognized. Sometimes the church “wrestled” in prayer, awaiting a breakthrough. Prayer was described as a sweet labor, a balm, a burden, and a pleasure. Bishop McKendree was sometimes criticized for seeming to command God during his intense public prayers. But upon his death it was written:

His piety was profound. Conscientiousness was a prominent trait in his character, and one more truthful in word and deed I never saw. He prayed much and regularly, took all his cares and wants to God in prayer. His standard of religion, experimental and practical, was a high one. He watched, prayed, fasted, and labored in earnestness. He was a holy man, loving God with all his heart and his neighbor as himself. No one ever was known to doubt his purity of character; in this he was a bright exemplar.

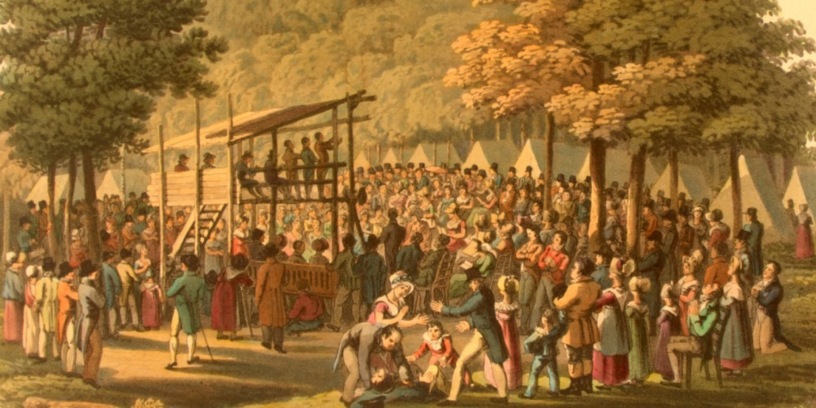

Revival

The early Methodist bishops served during the outbreak of frontier revivals that were not neatly aligned with any particular denomination. Baptist leaders often viewed these irregular, mixed gatherings with suspicion. Methodist bishops, however, embraced and supported them. Bishop Francis Asbury, “urged the presiding elders… to turn the summer Quarterly Conferences into camp meetings whenever feasible…. Asbury was convinced of the great spiritual benefits resulting from these outdoor revivals. His enthusiasm was expressed in the statement, ‘Methodists are all for camp meetings.’ He was well pleased when preachers reported successful camp meetings. He was, however, strongly opposed to the more fanatical behavior frequently seen and emphasized there should be order at all times.” (Kerstetter)

According to A History of Methodism in Kentucky, Vol. 1 by William Erastus Arnold, William McKendree was directly supportive of the revivals that broken out in Kentucky among the Methodists and Presbyterians, Cane Ridge being the largest. “When he went on toward Central and Northern Kentucky in his round, he told the people everywhere of the wonderful things the Lord was doing in Middle Tennessee and Western Kentucky.” (p. 197) Annual conference sessions were sometimes scheduled in conjunction with camp meetings.

Support for camp meetings came at a price. While spending a week in York during July 1807, Asbury noted in his journal “that the success of our labors, more especially at camp meetings, has roused a spirit of persecution against us — riots, fines, stripes, perhaps prisons and death, if we do not give up our camp meetings: we shall never abandon them, but shall subdue our enemies by overcoming evil with good.” Asbury recommended the deployment of respectable laymen carrying long, white peeled rods to maintain order and guard against attacks.

Evangelical Poverty

The early bishops modeled poverty and sacrifice. Like the young preachers they oversaw, most were unmarried and functionally homeless. The first salary on record for a bishop was $24 Pennsylvania dollars per year, plus travel expenses. They wore nothing to indicate their office in the church beyond the standard plain dress of circuit riders. This was quite a contrast to the episcopacy in other churches. On September 16, 1791, Asbury reflecting on the spiritual laxness in the more established sectors of the church:

“”A bishoprick with one, or two, or three thousand sterling a year as an appendage, might determine the most hesitating in their choice: I see no reason why a heathen philosopher, who had enough of this world’s wisdom to see the advantages of wealth and honors, should not say, ‘Give me a bishoprick and I will be a Christian.’ In the Eastern states also there are very good and sufficient reasons for the faith of the favored ministry. Ease, honor, interest: what follows –idolatry, superstition, death.”

Asbury did not suffer for the sake of suffering. He saw it as necessary to further the work of God. He wrote in his journal on May 20, 1792:

“Virginia. Rode twenty miles. My weary body feels the want of rest ; but my heart rejoiced to meet with the brethren who were waiting for me. I am more than ever convinced of the need and propriety of annual conferences, and of greater changes among the preachers. I am sensible the western parts have suffered by my absence; I lament this, and deplore my loss of strict communion with God, occasioned by the necessity I am under of constant riding ; change of place ; company, and sometimes disagreeable company; loss of sleep, and the difficulties of clambering over rocks and mountains, and journeying at the rate of seven or eight hundred miles per month, and sometimes forty or fifty miles a day—these have been a part of my labors, and make no small share of my hinderances.”

Church Discipline

The bishops had the unenviable task of correcting and removing preachers for doctrinal, character, and other issues. In perhaps his most famous Letter (to Joseph Benson 1816), Asbury reflected on the reputation that the episcopacy had among the Baptists and Presbyterians as tyrants. But, he argues, the word “bishop” simply comes from the German “bischoff,” the chief minister:

“With us a bishop is a plain man, altogether like his brethren, wearing no marks of distinction, advanced in age, and by virtue of his office can sit as president in all the solemn assemblies of the ministers of the gospel; and many times, if he is able, called upon to labor and suffer more than any of his brethren; no negative or positive in forming Church rules; raised to a small degree of constituted and elective authority above all his brethren; and in the executive department, power to say, ‘Brother, that must not be, that cannot be,’ having full power to put a negative or a positive in his high charge of administration; and, even in the Annual Conference to correct the body or any individual that may have transgressed or would transgress and go over the printed rules by which they are to be governed, and bring up every man and everything to the printed rules of order established in the form of Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church in America.”

Conclusion

The hard labor of early Methodist bishops lent credibility to their task of shepherding a fast-growing movement in rapidly-changing times. Spiritual unity was a primary challenge and concern. Early bishops often judged a conference by the spirit of unity that was present as the group practiced self-examination in doctrine, character, and Christian experience. Consider these entries from Asbury’s journal:

- April 11, 1789, North Carolina: “We opened our conference, and were blessed with peace and union ; our brethren from the westward met us, and we had weighty matters for consideration before us.”

- February 13, 1790, Charleston: “The preachers are coming in to the conference. I have felt fresh springs of desire in my soul for a revival of religion. O may the work be general! It is a happy thing to be united as is our society; the happy news of the revival of the work of God flies from one part of the continent to the other, and all partake of the joy.”

- May 26, 1791, New York: “Our conference came together in great peace and love. Our ordinary business was enlivened by the relation of experiences, and by profitable observations on the work of God.”

But the nation itself was tearing apart and Methodists were in no way immune. In the next installment will cover the bishops’ role in the split that was, until recently, the largest division in Methodist history.

*Nathan Bangs describes the sermon in 1808 given by Bishop McKendree that may have led to his election as bishop: “The house was crowded with strangers in every part, above and below, eager to hear the stranger; and among others, most of the members of the General Conference were present, besides a number of colored people who occupied a second gallery in the front end of the church. Mr. McKendree entered the pulpit at the hour for commencing the services, clothed in very coarse and homely garments, which he had worn in the woods of the West, and, after singing, he kneeled in prayer. As was often the case with him, when he commenced his prayer he seemed to falter in his speech, clipping some of his words at the end, and occasionally hanging upon a syllable, as if it were difficult for him to pronounce the word. I looked at him not without some feeling of distrust, thinking to myself: “I wonder what awkward backwoodsman they have put in the pulpit this morning to disgrace us with his mawkish and uncouth phraseology?…At first, sodden shrieks, as of persons in distress, were heard in different parts of the house; then shouts of praise, and in every direction sobs, and groans, and eyes overflowing with tears, while many were prostrated upon the floor, or lay helpless on the seats. A very large athletic-looking preacher who was sitting by my side, suddenly fell upon his seat, as if pierced by a bullet; and I felt my heart melting under sensations which I could not well resist. “After this sudden shower, the clouds were disparted, and the sun of righteousness shone out most serenely and delightfully, producing upon all present a consciousness of the divine approbation; and when the preacher descended from the pulpit, all were filled with admiration of his talents, and were ready to magnify the grace of God in him, as a chosen messenger of good tidings to the lost, saying in their hearts, ‘This is the man whom God delights to honor.’ ‘This sermon.’ Bishop Asbury was heard to exclaim, ‘will make him a bishop.’ “This was a mighty effort, without any effort at all — for all seemed artless, simple, plain, and energetic, without any attempt at display or studied design to produce effect. An attempt, therefore, to imitate it would be a greater failure than has been my essay to describe it; and it would unquestionably lower the man’s character who should hazard the attempt, unless when under the influence of corresponding feelings and circumstances.”

A good example of a teaching, preaching Methodist bishop is Ricardo Pereira Diaz of la Iglesia Metodista en Cuba. They recently completed their campaign of revival & miracles that began with a time of prayer & fasting. They estimate a total of 91,000 attended the various meetings & 8,166 prayed for salvation. Many people walked out of their wheel chairs & threw away their crutches. Others received a variety of healings. Check out their Facebook page Iglesia Metodista en Cuba. They are no longer affiliated with the UMC.